Does this scenario sound familiar? Your company has embraced agile and teams now enjoy greater focus and clearer collaboration. Yet the anticipated business benefits have not materialized. Delivery is slow, expensive and a source of frustration.

Although agile has markedly improved organisations, the full benefits are unattainable unless the entire work system is aligned with agile principles.

With over 20 years of experience in helping organisations achieve high performance and adaptability, I've gained valuable insights into agile system design. In this article, I will share some of these insights and discuss one of the most effective frameworks for optimizing organizations for peak performance: value streams.

Organisational Design

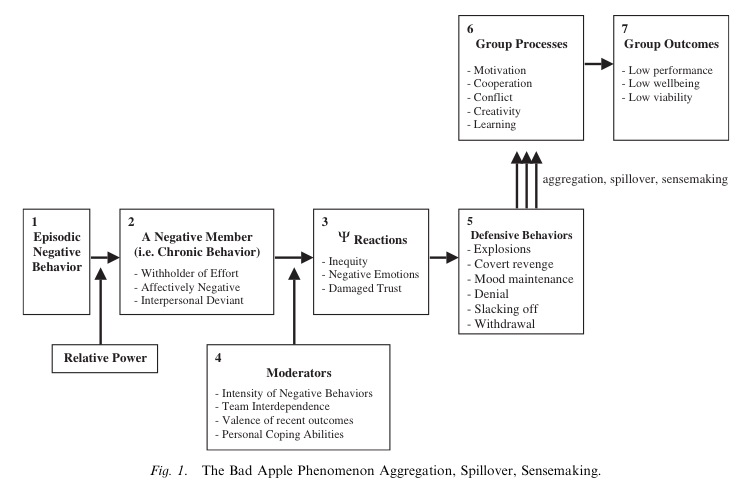

For the past century, reductionism has been the prevailing method of organizational design. In this model, the work of the organization is progressively broken down and assigned to functional units. Centralized management then coordinates these functions, aiming to ensure that the right people perform the right work at the right time. This approach has historically been reasonably effective, contributing to the development of many goods and services we now consider essential.

However, over the past three decades, as the world has grown increasingly fast & complex, the limitations of the reductionist approach have become painfully apparent. It presents several challenges:

- Frequent hand-offs between teams or business units that hinder rapid end-to-end delivery.

- Ambiguities in team roles and interactions, leading to internal friction and confusion.

- An inability for the organization to swiftly adapt to external market changes as work is stuck in progress.

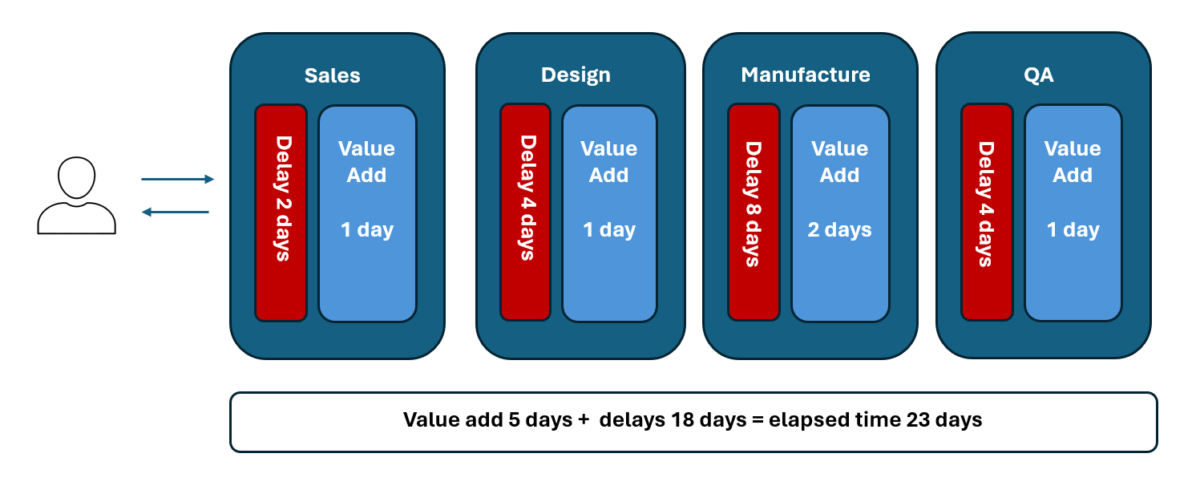

Consider a traditional organisation design where individuals are grouped based on their skills into specific functions, such as Sales, Marketing, Product, and R&D. When a customer makes a purchase or request, the responsibility for fulfilling this request flows across these various functions. Each participant handles their segment of the request before handing it off to the next function, like a relay race. If errors occur, the work must be returned to a previous stage for corrections.

Coordination of these efforts typically falls to a manager, whose task is to orchestrate these activities efficiently—a nearly impossible job. Often, when work arrives at a function, that group is already engaged with other tasks, forcing the new work to wait. This leads to significant delays.

Furthermore, since each group focuses only on their specific part of the process, they may lose sight of the overall customer outcome. This can lead to misdirected efforts and costly mistakes.

While a functional structure makes sense from an internal efficiency standpoint (let's group everyone who does similar work together), it creates significant waste and fails to streamline the delivery of value to the customer. And in a hyper-competitive world that just doesn't cut it.

Agile Emerges as a Team-Level Solution

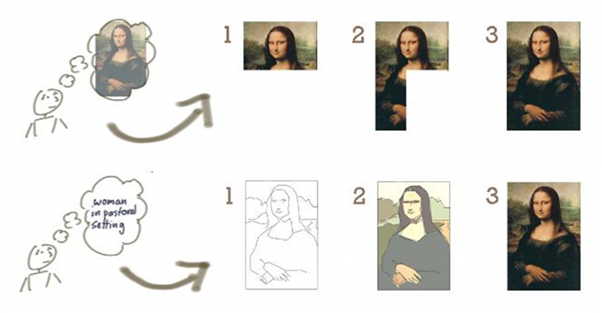

Agile provided major improvements at a team level via cross-functional teams. To eliminate hand-offs between functions, teams were cross-functional and worked collaboratively to deliver a shared customer outcome.

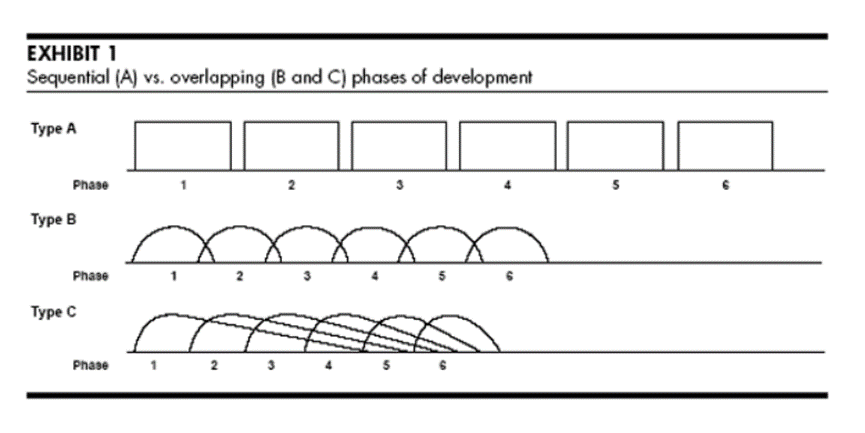

Jeff Sutherland, co-creator of Scrum, took inspiration from The New New Product Development Game.

"Under the rugby approach, the product development process emerges from the constant interaction of a hand-picked, multidisciplinary team whose members work together from start to finish. Rather than moving in defined, highly structured stages, the process is born out of the team members’ interplay (see Exhibit 1).

In the rugby approach to product development, a specially selected, multidisciplinary team collaborates continuously from the project's inception to its completion. The development process evolves through the dynamic interplay among team members, rather than progressing through rigid, predefined stages. This method emphasises the fluid and collaborative nature of the team's interactions (refer to Exhibit 1)."

Exhibit 1 - Sequential (A) vs. overlapping (B and C) phases of development

In a cross-functional scenario, a team would be made up of individuals from Sales, Marketing, Product, and R&D, all collaborating as a single unit with a clear focus on meeting the customer's needs. Progress!

However, complications arise when the work requires multiple teams. Handoffs lead to work accumulating in queues, awaiting the next person, team or business unit.

This delay is glaringly obvious in the production of physical goods, where work visibly stacks up. Consider a production line where goods must go through several stages to be completed. Queues immediately highlight where the bottlenecks are and we can identify areas to investigate.

Yet in knowledge work, the queues are largely invisible. Work sits in a queue, waiting for a team or business unit to pick up once they get what they are currently doing completed. Consider all the items sitting in your email inbox, pending your action to move forward!

In many organizations, only 5-10% of the total time required to deliver a piece of work is the time spent actively working on it (adding value). The rest, a staggering 90-95%, is spent waiting. This is known as process efficiency and understanding this can fundamentally change how you view organisation design.

The traditional functional organisation design results in significant waste. The value-add work is only 5 days yet elapsed time is 23 days. This is surprisingly common.

Value Streams

Agile revolutionized more than just software development, quickly gaining traction with other business units such as legal, finance, and marketing.

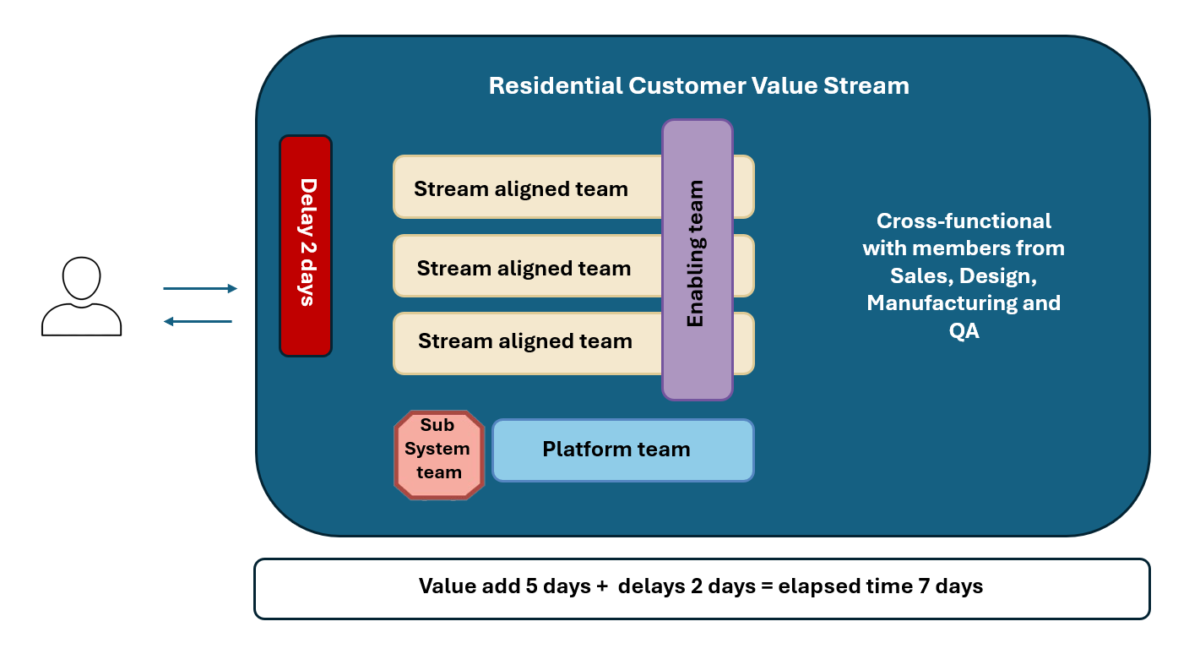

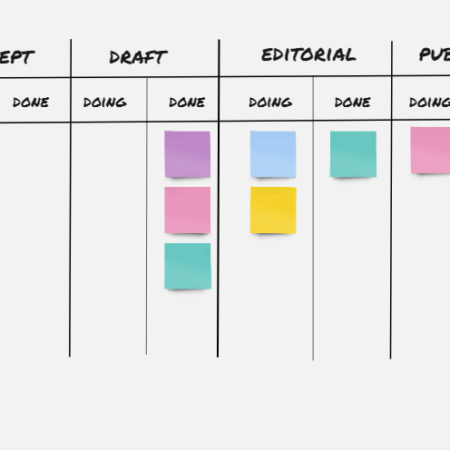

Value Streams extend the agile philosophy into organizational design by organizing multiple teams around a clear, customer-oriented mission, aiming to minimize hand-offs and establish clear team scope and interactions. By aligning cross-functional teams towards a unified goal, value streams reduce unnecessary hand-offs and have become an essential element of contemporary organizational design.

In a Value Stream-based model, the design is optimized to reduce hand-offs and wait times, with clearly defined team scopes and interactions.

When structuring teams, Team Topologies by Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais offers valuable guidance. It outlines four distinct team topologies:

- Stream-aligned team: aligned to a flow of work from (usually) a segment of the business domain

- Enabling team: helps a Stream-aligned team to overcome obstacles. Also detects missing capabilities.

- Complicated Subsystem team: where significant mathematics/calculation/technical expertise is needed.

- Platform team: a grouping of other team types that provide a compelling internal product to accelerate delivery by Stream-aligned teams

Leveraging Value Streams

While value streams are a highly beneficial concept, adopting a value stream-based operating model represents a significant undertaking. It alters the fundamental ways in which people work, disrupting roles, accountabilities, reporting structures, and performance metrics. Managing this transition requires strong change management.

Such transformations are inherently risky. Each organization possesses a unique blend of people, processes, culture, mindset, governance, management, and leadership. Successfully implementing a value stream model involves thorough consideration, meticulous planning, and careful adaptation.

We have achieved considerable success using a strategy that involves co-creation with stakeholders and pilots.

Co-creating a Value Stream Operating Model

Co-creation involves collaborative workshops where we design the operating model together. Our approach is grounded in the belief that while Radically provides deep expertise, no one understands the intricacies of your business as well as you do.

Our clients consistently tell us that this collaborative approach is a breath of fresh air. Many have had negative experiences with traditional consulting firms that isolate themselves in a conference room for weeks before unveiling their model in a grand reveal. Experiencing change imposed upon you can be unpleasant. Participating in the process of change is far more empowering.

Naturally, no model is flawless. This type of work is fraught with complexities and many "unknown unknowns." This is where conducting pilot projects proves invaluable, allowing for iterative testing and refinement.

Pilots

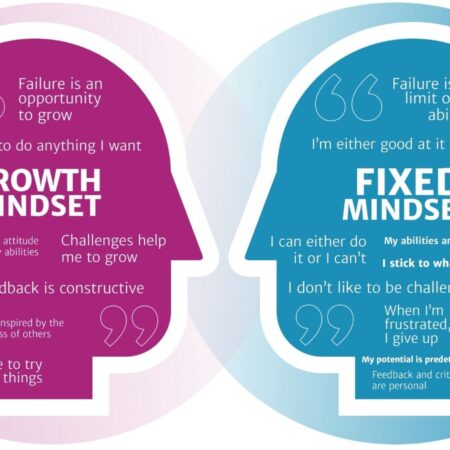

The field of Complex Adaptive Systems has significantly influenced our understanding of organizational design. Such systems, characterized by "unknown unknowns," defy straightforward planning and implementation. Instead, effective solutions tend to emerge organically through active engagement and practical experimentation.

The purpose of a pilot is to implement a crucial piece of work using agile, uncovering likely "unknown unknowns" before scaling further. Typically, a pilot focuses on a specific segment of the business, such as a single value stream, a strategic initiative, or a major project. At Radically, we establish these pilots based on the principles, desired culture, leadership style, and operational methods we aim to promote.

We assemble a cross-functional team drawn from different business units. Their role is to

- Guide the change.

- Observe the emerging patterns and interactions.

- Use the insights gained from these observations to refine and enhance the operating model design.

In this approach, we work in short cycles, continuously reviewing and adjusting our progress. During these iterations, we identify any aspects that may need modification to successfully scale the model, such as reporting structures, incentive schemes, key performance indicators, mindsets, skills, and communication methods. Over several months, this iterative process yields critical insights—insights that only become apparent through actual implementation. We then determine solutions for these issues before scaling further.

By leveraging co-creation and pilot projects, we collaboratively design and test a model that truly works. When the people doing the work participate in the model design, it not only enables smoother change but also makes acceptance and adaptation of the model substantially easier.

Summary

Adopting a value stream-based operating model can significantly reduce waste and increase adaptability across many organizations. When combined with agile ways of working, human leadership, and a strong emphasis on value, companies can greatly enhance both performance and customer satisfaction, while also improving organizational culture and the workplace experience for their employees.

Designing such an operating model involves numerous collaborative design workshops, effective communication, active listening, and thoughtful discussions, all underpinned by careful change management. Strong executive sponsorship and support are crucial; without this model being a priority among the top executive concerns, successful implementation is unlikely. Transitioning to a new operating model is a substantial and disruptive endeavour, but the benefits make it a worthwhile investment.

Want to learn more?

If you’d like to learn more, we can run a one-day deep dive Designing Value Streams workshop for you. Just drop me a line and we can discuss.

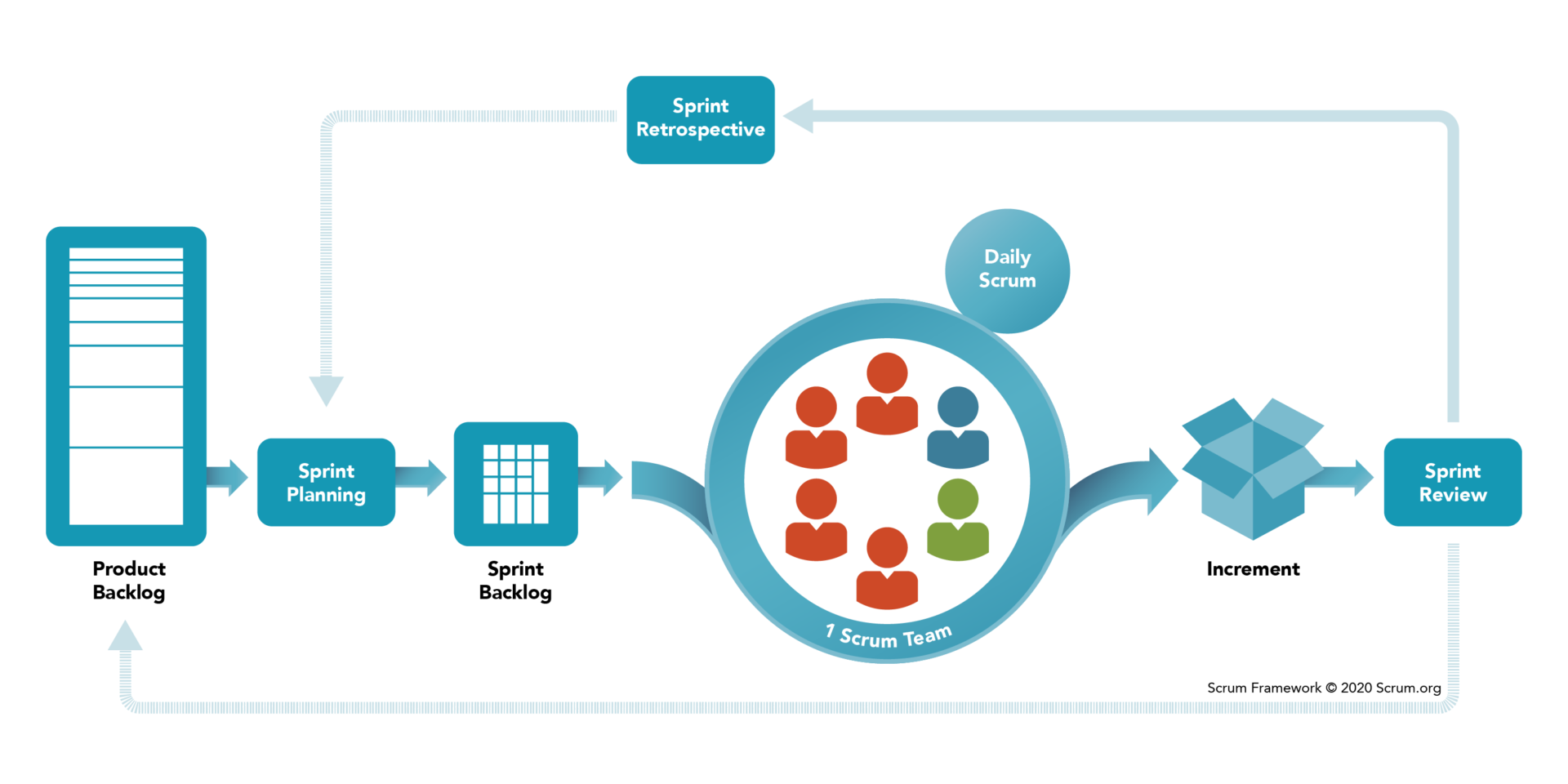

The iterative, incremental nature of Scrum can help to bring focus, commitment, alignment and collaboration to the forefront of your business.

The iterative, incremental nature of Scrum can help to bring focus, commitment, alignment and collaboration to the forefront of your business.

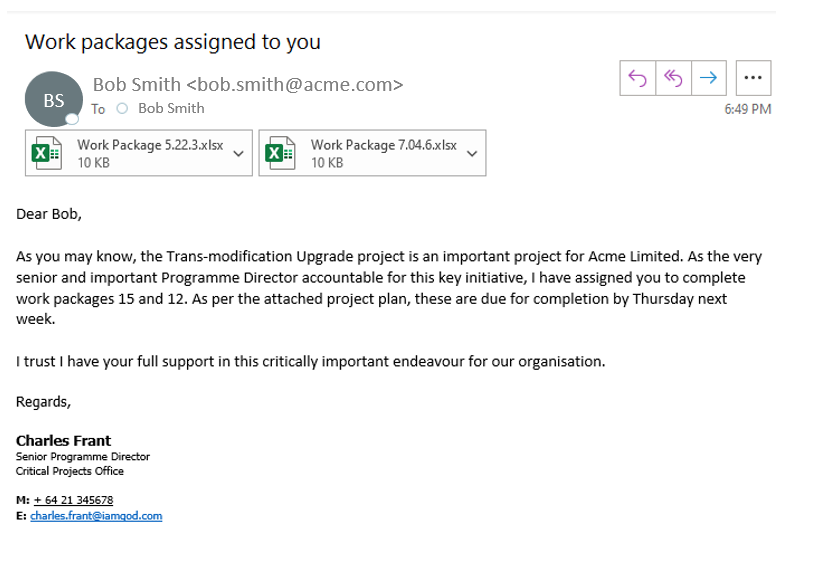

It turned out this was happening everywhere. There were literally thousands of invisible undercurrents running all the way through the organisation based on whatever work well-meaning managers were trying to get done. They had no transparency of what was actually going on.

It turned out this was happening everywhere. There were literally thousands of invisible undercurrents running all the way through the organisation based on whatever work well-meaning managers were trying to get done. They had no transparency of what was actually going on.